“This is the time that we, who have benefitted from the Last Poets should

be able to say, ‘it’s the Last Poets. It’s them we should be honouring,

because we did not honour them for so many years_”

KRS One wasn’t just addressing the hip hop fraternity when he uttered

those words by way of introducing the video for Invocation – a poem

written thirty years ago, around the time of the Last Poets’ last significant

comeback. He was speaking to everyone who’s been affected by the

word, sound and power issuing from the most revolutionary poetry ever

witnessed, and that the Last Poets had introduced to the world outside of

Harlem at the dawn of the seventies.

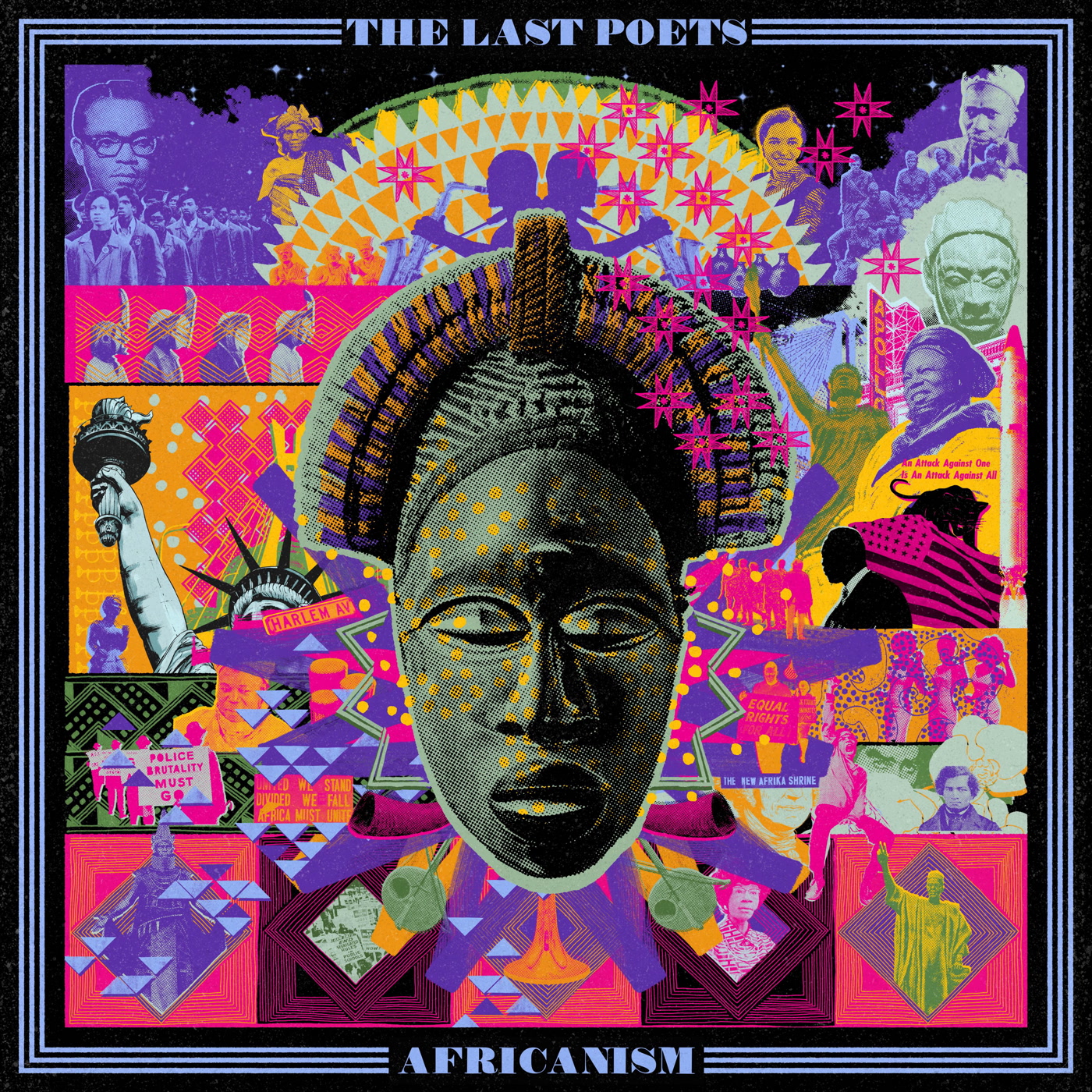

In 2018 the two remaining Last Poets, Abiodun Oyewole and Umar Bin

Hassan, embarked on another memorable return with an album –

Understand What Black Is – that earned favourable comparison with their

seminal works of the past, whilst showcasing their undimmed passion and

lyrical brilliance in an entirely new setting – that of reggae music. Tracks

like Rain Of Terror (“America is a terrorist”) and How Many Bullets

demonstrated that they’d lost none of their fire or anger, and their

essential raison d’etre remained the same.

“The Last Poets’ mission was to pull the people out of the rubble o f their

lives,” wrote their biographer Kim Green. “They knew, deep down that

poetry could save the people – that if black people could see and hear

themselves and their struggles through the spoken word, they would be

moved to change.”

Several years later and the follow-up is now with us. The project started

when Tony Allen, the Nigerian master drummer whose unique

polyrhythms had driven much of Fela Kuti’s best work, dropped by Prince

Fatty’s Brighton studio and laid down a selection of drum patterns to die

for. That was back in 2019, but then the pandemic struck. Once it had

passed, the label booked a studio in Brooklyn, where the two Poets voiced

four tracks apiece and breathed fresh energy, fire and outrage into some

of the most enduring landmarks of their career. Abiodun, who was one of

the original Last Poets who’d gathered in East Harlem’s Mount Morris Park

to celebrate Malcolm X’s birthday in May 1968, chose four poems that

first appeared on the group’s 1970 debut album, called simply The Last

Poets. He’d written When The Revolution Comes aged twenty, whilst living

in Jamaica, Queens. “We were getting ready for a revolution,” he told

Green. “There wasn’t any question about whether there was going to be

one or not. The truth was many of us still saw ourselves as “niggers” and

slaves. This was a mindset that had to change if there was ever to be

Black Power.”

He and writer Amiri Baraka were deep in conversation one day when

Baraka became distracted by a pretty girl walking by. “You’re a gash

man,” Abiodun told him. The poem inspired by that incident, Gash Man, is

revisited on the new album, and exposes the heartless nature of sexual

acts shorn of intimacy or affection. “Instead of the vagina being the

entrance to heaven,” he says, “it too often becomes a gash, an injury, a

wound_”

Two Little Boys meanwhile, was inspired after seeing two young boys

aged around 11 or 12 “stuffing chicken and cornbread down their

tasteless mouths, trying to revive shrinking lungs and a wasted mind.”

They’d walked into Sylvia’s soul food restaurant in Harlem, ordered big

meals, then bolted them down and run out the door. No one chased after

them, knowing that they probably hadn’t eaten in days. Fifty years later

and children are still going hungry in major cities across America and

elsewhere. Abiodun’s poem hasn’t lost any relevance at all, and neither

has New York, New York, The Big Apple. “Although this was written in

1968, New York hasn’t changed a bit,” he admits, except “today, people

just mistake her sickness for fashion.”

Umar is originally from Akron, Ohio, but had arrived in Harlem in early

1969 after seeing Abiodun and the other Last Poets at a Black Arts

Festival in Cleveland. That’s where he first witnessed what Amiri Baraka

once called “the rhythmic animation of word, poem, image as word-

music” – a creative force that redefined the concept of performance

poetry and stripped it bare until it became a howl of rage, hurt and anger,

saved from destruction by mockery and love for humanity. When Umar’s

father, who was a musician, was jailed for armed robbery he took to the

streets from an early age where he shined shoes and raised whatever

money he could to help feed his eight brothers and sisters. By the time he

saw the Last Poets he’d joined the Black United Front and was ready to

join the struggle.

Once in Harlem, Abiodun asked him what he’d learnt in the few weeks

since he’d got there. “Niggers are scared of revolution,” Umar replied.

“Write it down” urged Abiodun. That poem still gives off searing heat

more than fifty years later. In Umar’s own words, “it became a prayer, a

call to arms, a spiritual pond to bathe and cleanse in because niggers are

not just vile and disgusting and shiftless. Niggers are human beings lost

in someone else’s system of values and morals.”

And there you have it. It’s not just race or religion that hold us back, but

an economic system that keeps millions in poverty and living in fear – a

system born from political choice and that’s now become so entrenched,

so bloated on its own success that it’s put mankind in mortal danger. It

was many black people’s acceptance of the status quo that inspired Just

Because, which like Niggers Are Scared Of Revolution, was included on

that seminal first album. Along with their revolutionary rhetoric, it was the

Last Poets’ use of the “n word” that proved so shocking, but it would be

wrong to suggest that they reclaimed it, since it never belonged to black

people in the first place. There’s never any hiding place when it comes to

the Last Poets. They use words like weapons, and that force all who listen

to decide who they are and where they stand.

Umar’s two remaining tracks find him revisiting poems first unleashed on

the Poets’ second album This Is Madness! Abiodun had left for North

Carolina by then where he became more deeply enmeshed in

revolutionary activities and spent almost four years in jail for armed

robbery after attempting to seize funds related to the Klu Klux Klan.

Meanwhile, the 21 year old Umar was squatting in Brooklyn and had

developed close ties with the Dar-ul Islam Movement. A longing for purity

and time-honoured spiritual values underpins Related to What, whilst This

Is Madness is a call for freedom “by any means necessary,” and that

paints a feverish landscape peopled by prominent black leaders but that

quickly descends into chaos. “All my dreams have been turned into

psychedelic nightmares,” he wails, over a groove now powered by Tony

Allen’s ferocious drumming.

Those sessions lasted just two days, and we can only imagine the

atmosphere in that room as the hip hop godfathers exchanged the conga

drums of Harlem for the explosive sounds of authentic Afrobeat. Once

they’d finished, the recordings and momentum returned to Prince Fatty’s

studio, since relocated from Brighton to SE London. This was stage three

of the project, and who better to fill out the rhythm tracks than two key

musicians from Seun Anikulapo Kuti’s band Egypt 80? Enter guitarist

Akinola Adio Oyebola and bassist Kunle Justice, who upon hearing Allen’s

trademark grooves exclaimed, “oh, the Father_ we are home!” Such joy

and enthusiasm resulted in the perfect fusion of Nigerian Afrobeat and

revolutionary poetry, but the vision for the album wasn’t yet complete. He

wanted to create a new kind of soundscape – one that reunited the Poets

with the progressive jazz movement they’d once shared with musicians

like Sun Ra and Pharoah Sanders. It was at that point they recruited

exciting jazz talents based in the UK like Joe Armon Jones from Mercury

Prize winners Ezra Collective, also widely acclaimed producer/remixer and

keyboard player Kaidi Tatham, who’s been likened to Herbie Hancock, and

British jazz legend Courtney Pine, whose genius on the saxophone and

influence on the UK’s now vibrant jazz scene is beyond question.

The instrumental tracks on Africanism are in many ways as revelatory and

exciting as the Last Poets’ own. It’s important to remember that the

kaleidoscope of styles and influences we’re presented with here aren’t the

result of sampling but were played “live” by musicians responding to

sounds made by other musicians. That’s where the magic comes from,

aided by Prince Fatty’s peerless mixing which allows us to hear everything

with such clarity. Music fans today have grown accustomed to listening to

all kinds of different genres. Their tastes have never been so broad or all-

encompassing, and so the music on this new Last Poets’ album is as

groundbreaking as their lyrics, and perfectly suited to the era that we’re

now living in.

John Masouri